A Collection of Meysam’s work will be opening at the Dedee Shattuck Gallery on September 22nd at 6pm. Professor Karimi will speak at 6:30. Gallery will be open September 23, 24, 30 and 31 from 12-5pm. Please RSVP on Facebook or Eventbrite.

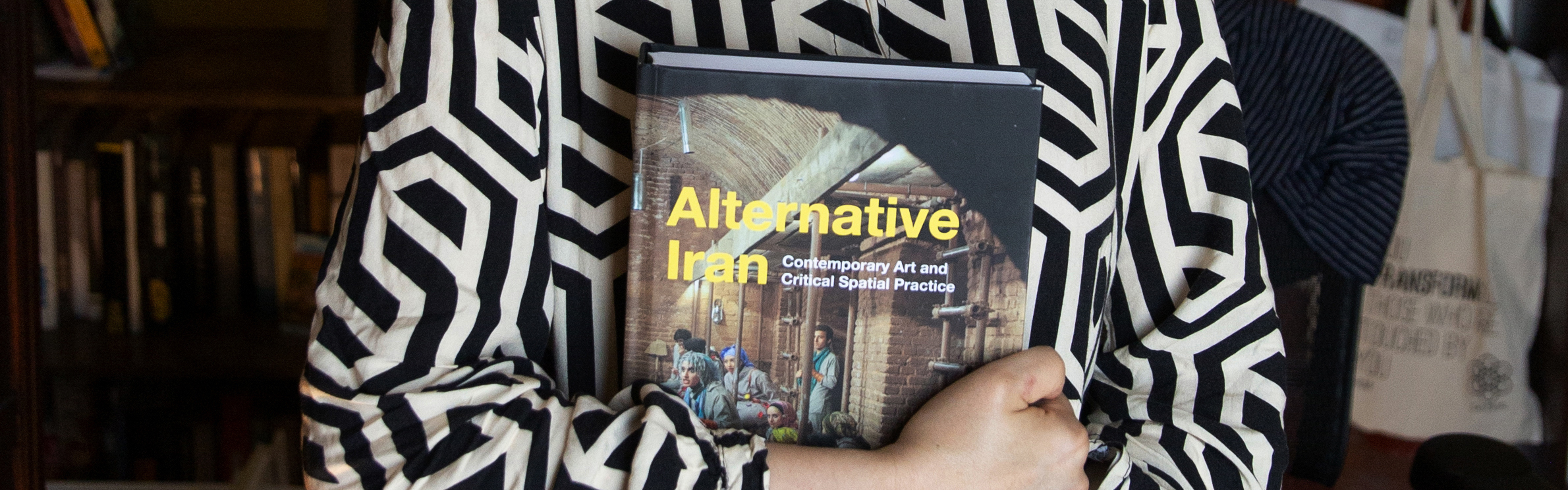

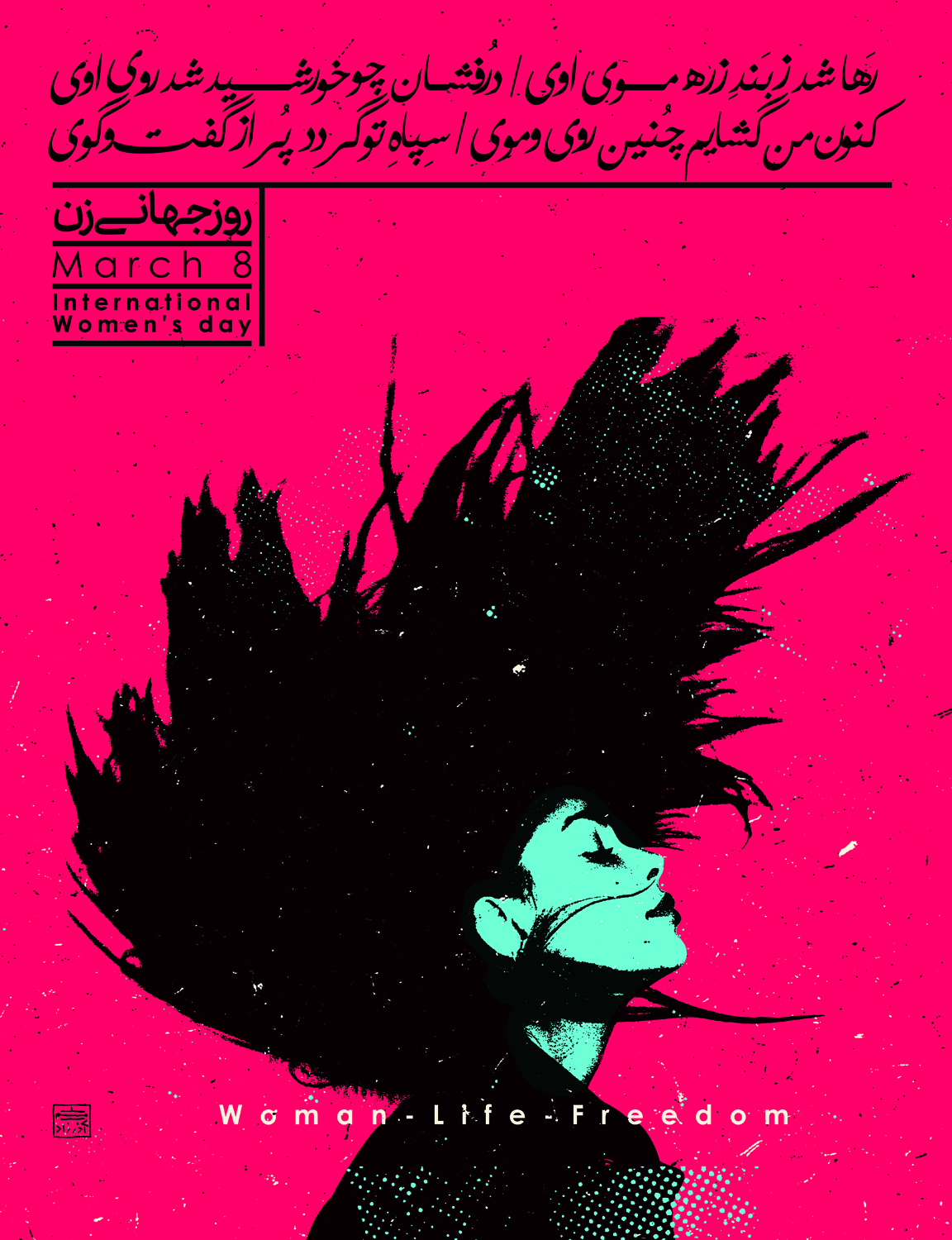

Pamela Karimi is a Professor of History of Art and Architecture at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. She is the author of Domesticity and Consumer Culture in Iran and Alternative Iran: Contemporary Art and Critical Spatial Practice. In the wake of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising, Karimi has penned numerous articles and delivered lectures, highlighting the pivotal role of art in the movement. Since joining the University of Massachusetts in 2009, she has curated various exhibitions. Of particular note is this solo exhibition at Deedee Shattuck Gallery, featuring Meysam Azarzad’s activist art. The exhibition draws from Karimi’s ongoing research into the intersections of art and activism in Iran and marks the anniversary of the uprising in September 2022.

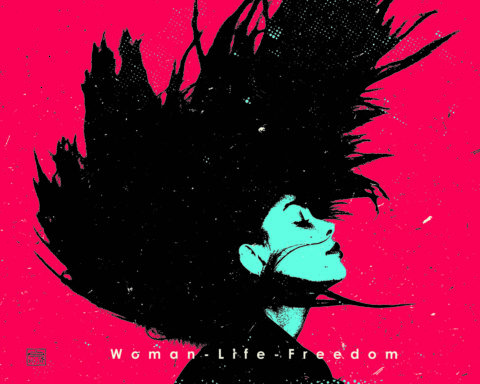

Merri Cyr: What first struck me when I viewed Meysam Azarzad’s works was the recurring phrase: “Woman, Life, Freedom.” Can you elaborate on its significance?

Pamela Karimi: In September 2022, Mahsa Amini, a Kurdish woman from a small city in Iran, visited Tehran wearing a loosely tied scarf, typical of many Iranian women. Iran mandates the wearing of hijab in public spaces, and Mahsa’s attire was deemed inappropriate by the morality police—a division that ensures public adherence to Islamic norms. They arrested her, and tragically, she was reportedly beaten and subsequently died from her injuries.

Her death ignited widespread protests in Iran, that soon became known as “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests, which is occasionally referred to as “Women, Life, Freedom”. This phrase originally emerged from the Kurdish National Liberation Movement in Turkey and was popularized by Kurdish feminist groups and Abdullah Öcalan, a political prisoner and founding member of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party. There is no direct political connection between Iran’s uprising and these movements. However, given Mahsa’s Kurdish background, the name aptly represented the uprising in Iran, that led to intense confrontations between the public and state authorities.

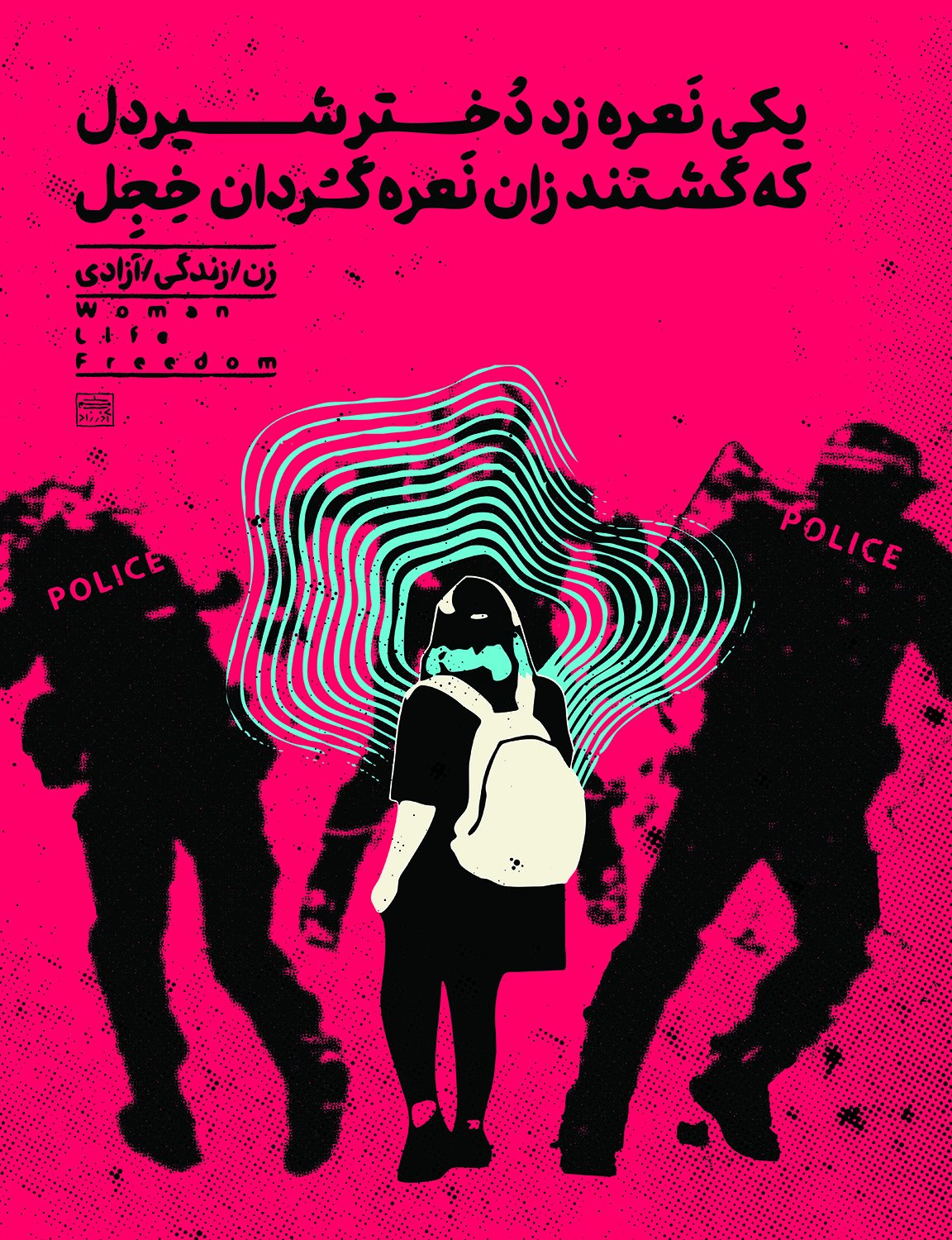

In response, Iranian artists created poignant artworks symbolizing the struggle, which they primarily shared on popular platforms like Instagram. These pieces not only circulated online but became integral visuals for the protests, appearing on banners, posters, and graffiti throughout Iranian cities. These influential visual materials played a role in sustaining the protests for approximately seven months.

MC: Can you describe the pieces featured in Meysam Azarzad’s solo exhibition at the Dedee Shattuck Gallery set to open on September 22nd?

PK: The exhibition showcases the work of Iranian artist Meysam Azarzad, known on Instagram as @m.az.za. Uniquely, Meysam documented the uprising from its beginning in September 2022, capturing the escalating tensions between Iranians and state authorities. He continues to create art that highlights the ongoing experiences of detained protesters.

Many Iranians feel the protests are ongoing. To express dissent against the Islamic Republic’s restrictions, some women no longer wear the veil or carry scarves, while others directly challenge authorities on the ground in various Iranian cities. The resistance also continues online and through various events, much of which take place outside Iran, like panel discussions, music performances, and academic roundtables.

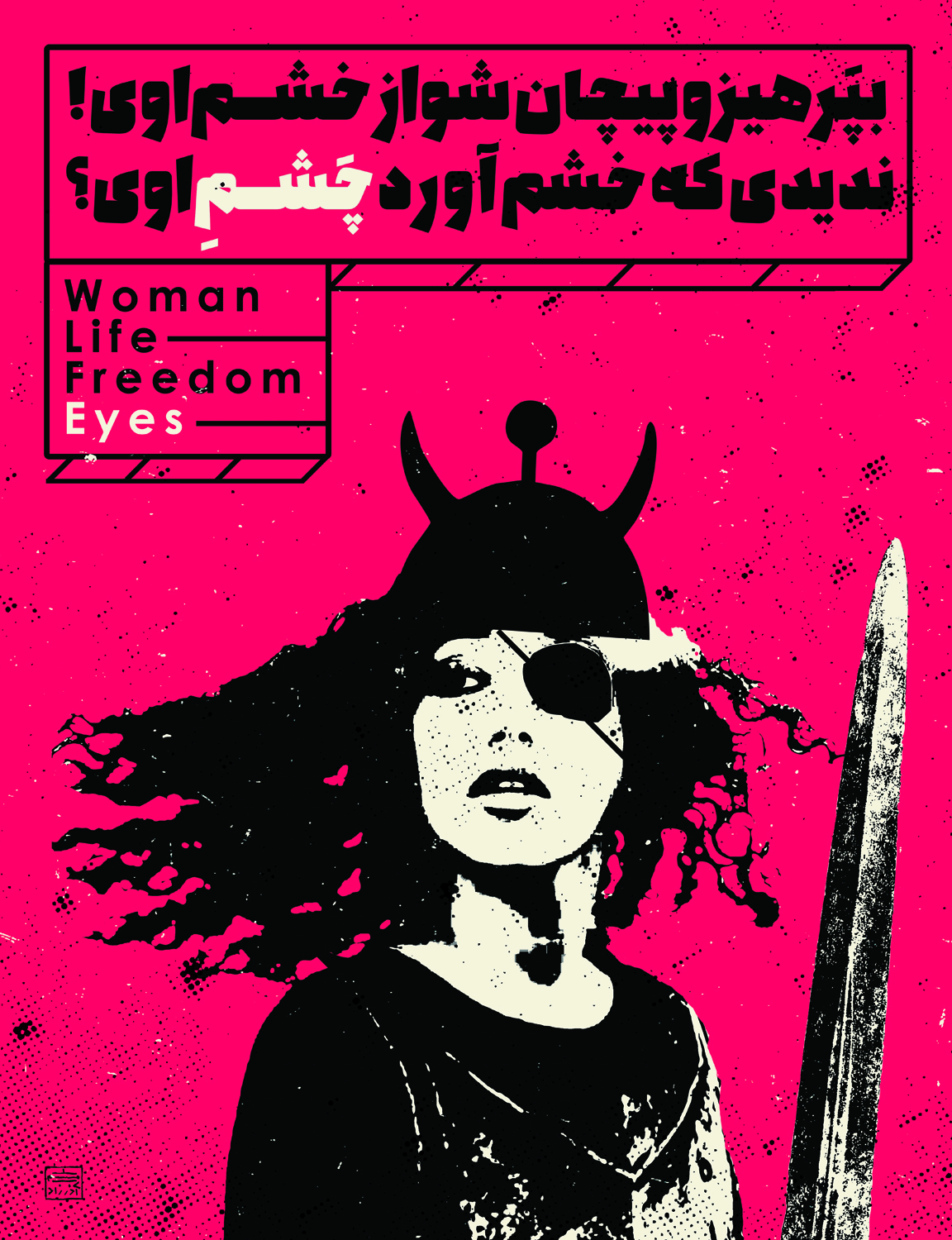

Returning to Meysam’s work, his art primarily features portraits of protesters, both those who suffered and those continuing the fight. He also showcases figures who have become symbolic heroes. Each portrait is paired with couplets from the poetry of Abolghassem Ferdowsi, Iran’s national poet. Ferdowsi’s seminal work, The Book of Kings or Shahnameh, written between the 10th and 11th centuries, remains relatable to all Iranians. Despite being a medieval text, its language is understood and often recited by Iranians, even inspiring revolutionary songs.

The Islamic Republic once attempted to suppress Ferdowsi’s writings because of their critical undertones towards invaders and Shahnameh’s celebration of Iran’s ancient past and clear distance from the traditions that became part of Iranian culture after the introduction of Islam. Though Islam has become an integral part of Iranian culture, the Islamic Republic’s laws, particularly those imposed on women, have led some to view religious affiliations as extremely restrictive. Ferdowsi’s poems, with their occasionally defiant tone, resonate with this modern movement, which is why they feature prominently in Meysam’s work.

Meysam sometimes modifies or blends the original couplets taken from longer poems of the Shahnameh, occasionally he also incorporates verses from other poets inspired by Ferdowsi. To Persian speakers, these adaptations have a revolutionary feel. His combination of powerful imagery with national poetry resonates both domestically and globally. This body of work is not just art; for many, it’s a testament to the current movement, even hinting at the potential for a revolution.

For Meysam, as well as many other Iranians, documenting this uprising is essential. They aim to highlight the sacrifices made in the pursuit of a democratic Iran for both present and future generations. The “martyrs” of this movement will always be remembered.

MC: How do you think the current political climate is influencing artists in Iran?

PK: Political art in Iran has a long history, especially following the 1979 Islamic Revolution. As I have discussed in my book, Alternative Iran: Contemporary Art and Critical Spatial Practice (SUP, 2022), initially, this art was mostly underground and subtle in its tone. However, since September 2022, the attitude has shifted. Artists like Meysam have adopted a more direct and bold approach. Many Iranians say there’s no going back to the cautious styles of the past, a change I find commendable for its bravery.

Most of this new art can’t gain official approval for public display from Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. Yet, artists find innovative ways to share their work. Some display it in galleries or public spaces without state permission, or in exclusive private, underground, and alternative venues. Others share their art internationally and on social media, often using aliases and frequently changing handles for safety.

MC: Women are the targets of the current violence in Iran. How have they reacted?

PK: Iranian women are now more assertive and courageous. Many of them step out in public without veils, despite it being illegal. Their rationale is that if enough women do this, the government can’t penalize everyone. While there have been instances of intimidation, harassment, and arrest from the morality police, these women have largely been successful in challenging societal norms. Since September 2022, there’s been a noticeable shift in how women dress in public. Similarly, art has transitioned from a cautious approach to a bolder, direct expression. This change represents the refusal to remain suppressed by state authorities.

MC: It seems to me that there’s a distinct Iranian perspective predating the introduction of Islam that still persists today. My understanding is that Iranians retain a distinctive identity. Can you elaborate on this?

PK: Definitely. This distinction is evident in how the Persian language persisted despite Arabic influences. This is quite distinctive. Arabic is undoubtedly a beautiful and rich language and it’s widely spoken in various regions of the Islamic world and beyond; however, Iran chose to retain Persian. Several factors contributed to this outcome, but many also attribute it to Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. His poetic works in Persian helped elevate the language. His rhythmic poetry, especially memorable for the youth, played a pivotal role. Additionally, for centuries, Iranian artists translated tales from the Shahnameh into vivid paintings. These illustrated renditions of the poems span various dynasties and regions of the Persianate world, from Iran to Central Asia, India, and even the Ottoman Empire. Another testament to Iran’s distinct identity is their preservation of memories from the pre-Arab civilizations, like the Achaemenid era or the Sassanian dynasty. Interestingly, Greek texts and their translations have historically provided insight into the Persian Empire.

MC: I guess it is surprising to me that a single poet can have so much influence on a culture.

PK: Certainly, Ferdowsi plays a significant role. However, it’s worth noting that during the Pahlavi era (1925-1979), both Mohammad Reza Shah and his father, Reza Shah, celebrated this poet. Multiple generations were urged to study Ferdowsi’s poems throughout their schooling. His tomb in northeastern Iran was transformed into a grand monument in the early Pahlavi years, and statues of him were erected in city centers. Thanks to the Pahlavi dynasty’s efforts, Ferdowsi’s cultural influence has remained very prominent. Although his poems were no longer a curriculum staple of post-revolutionary Iran, they’ve seen a revival, particularly as they’re incorporated into contemporary popular music. Indeed, in contemporary culture, classical poems are experiencing a resurgence, being transformed into revolutionary songs, rap music, and integrating into popular music trends.

MC: What is the significance of showcasing Meysam’s work in mid-September?

Meysam Azarzad was born in 1985 in Tehran, Iran. At the age of fifteen, he embarked on his professional illustration journey, collaborating with multiple publications within Tehran. Later, he chose to study graphic design in college. For seven years, Azarzad delved deeply into press illustrations, caricature design, and writing. His passion for animation subsequently steered him to professional roles in character and background design at various animation studios in Tehran. This progression marked the onset of a 15-year commitment to not only editing and scriptwriting but also directing and producing across diverse platforms such as cinema, video art, music videos, video advertisements, and motion graphics.

An artist with a broad spectrum, Azarzad has crafted and delivered over 200 advertising and video art projects. He has penned and directed two medium-length films, two short narrative films, and several documentaries. Furthermore, he has imparted his knowledge of motion graphics by teaching in Tehran. Demonstrating versatility in his craft, Azarzad has participated in countless group exhibitions showcasing caricature and illustration, both within Iran and on the international stage. His unparalleled skills have garnered him a plethora of awards in caricature, graphic design, animation, and video art from festivals both at home and abroad.

In 2009, due to his participation in the Green Movement protests, Azarzad endured incarceration at Evin, Tehran’s infamous political detention center. Today, while maintaining his activist stance expressed through art, he thrives as a freelancer spanning various media forms.